Coal formation

All living plants store solar energy through a process known as photosynthesis. When plants die, this energy is usually released as the plants decay. Under conditions favourable to coal formation, the decaying process is interrupted, preventing the release of the stored solar energy. The energy is locked into the coal.

Coal formation began during the Carboniferous Period – known as the first coal age – which spanned 360 million to 290 million years ago. The build-up of silt and other sediments, together with movements in the earth’s crust – known as tectonic movements – buried swamps and peat bogs, often to great depths. With burial, the plant material was subjected to high temperatures and pressures. This caused physical and chemical changes in the vegetation, transforming it into peat and then into coal.

Coalification

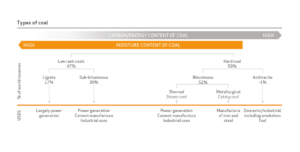

The degree of change undergone by a coal as it matures from peat to anthracite is known as coalification. Coalification has an important bearing on coal’s physical and chemical properties and is referred to as the ‘rank’ of the coal. Ranking is determined by the degree of transformation of the original plant material to carbon. The ranks of coals, from those with the least carbon to those with the most carbon, are lignite, sub-bituminous, bituminous and anthracite.

The quality of each coal deposit is determined by:

- Types of vegetation from which the coal originated

- Depths of burial

- Temperatures and pressures at those depths

- Length of time the coal has been forming in the deposit

Types of coal

Initially the peat is converted into lignite or ‘brown coal’ – these are coal-types with low organic maturity. In comparison to other coals, lignite is quite soft and its colour can range from dark black to various shades of brown.

Over many more millions of years, the continuing effects of temperature and pressure produces further change in the lignite, progressively increasing its organic maturity and transforming it into the range known as ‘sub-bituminous’ coals. Further chemical and physical changes occur until these coals became harder and blacker, forming the ‘bituminous’ or ‘hard coals’.

Under the right conditions, the progressive increase in the organic maturity can continue, finally forming anthracite.

In addition to carbon, coals contain hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen and varying amounts of sulphur. High-rank coals are high in carbon and therefore heat value, but low in hydrogen and oxygen. Low-rank coals are low in carbon but high in hydrogen and oxygen content. Different types of coal also have different uses.